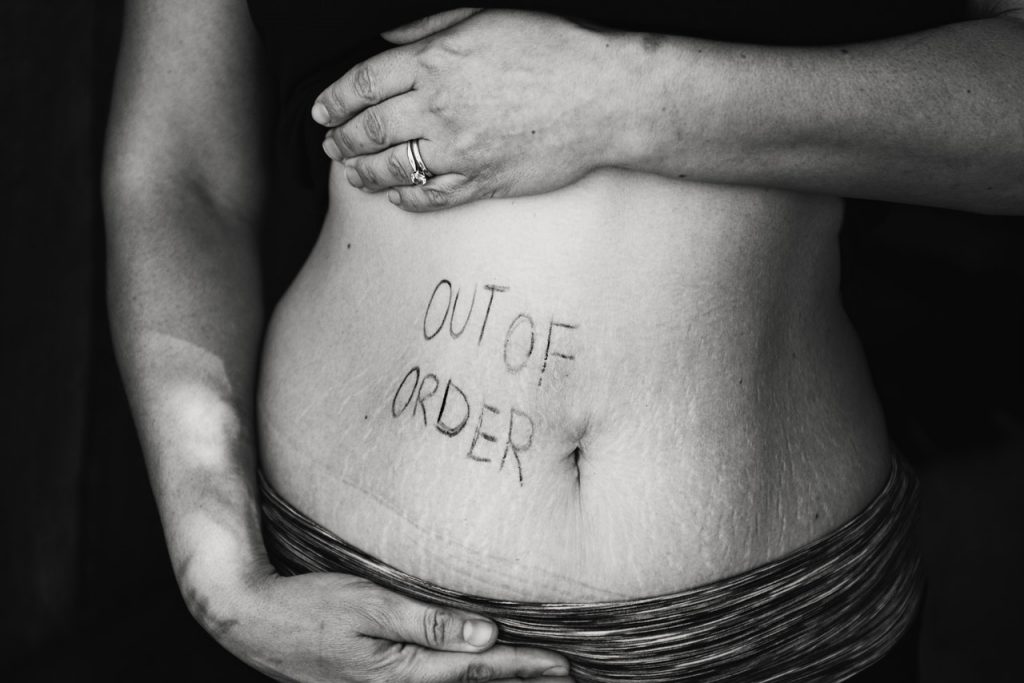

Photo courtesy of Aysia Stieb

Loss, Launch, and Ashtanga: One Visual Activist’s 2020 Story

Loss, Launch, and Ashtanga: One Visual Activist’s 2020 Story

After a decade working as a photo editor and producer, Sara Urbaez launched an online photography platform, LISTO, earlier this year. A powerful

protest against colonialism in photography, LISTO elevates the work of BIPOC photographers through artists’ series

and curated group shows. The images on LISTO are often taken by artists in their own communities, giving the visual

storytelling the depth it deserves.

Part of what’s so captivating about the artists’ series on LISTO are the accompanying interviews. Whether

discussing the many ways the industry fails BIPOC photographers or where an artist is from or even childbirth

(Urbaez also volunteers as a full-spectrum doula, serving marginalized communities), each conversation gives a

deeper understanding of the artist’s perspective.

Urbaez has made all this happen in less than a year—and she’s made it happen this year. An inspiring 2020

journey, yes, but one that has not been without its turning points and tragedies. She spoke with goop about

launching LISTO, experiencing loss, and the practice that has supported her through it all.

A Q&A with Sara Urbaez

I’d wanted to create my own platform that honored BIPOC for a long time, but I was hesitant about it. I think I had rigid ideas about what it needed to look like to be successful versus the skills that I had to do it well. Then, in April 2020, I lost my job and, in that same week, lost a family member to COVID. I had this moment of clarity when I knew it was finally the time for me to start LISTO. I have an amazing yoga teacher, Timothy Lynch, and a strong yoga community here in Berkeley, California, and around this time, I discovered through my practice just how rigidly I’d been focused on achieving things rather than really experiencing them.

I started to apply my learnings from yoga to help found LISTO. Mainly, I embraced the realization that all I needed to do was show up each day and do what I could. In April, I reached out to Tiffany Chan, who is now the platform’s design director. I began working on LISTO with the mindset of meeting myself where I was each day. It did not need to be perfect. It was that moment, in the beginning of the pandemic when everything was changing, that I didn’t feel the need to look for someone else’s approval. It was the time for me to create a space for other artists that I’d always wished I had.

Image courtesy of Adriana Loureiro Fernández

Exactly. And I started to understand that I didn’t need permission. I didn’t need to ask my boss or anyone else, “Oh, does this look okay? Is this artist okay?” I’ve been in the photography industry for close to ten years. I know what I care about. I know my point of view. I have no need to consult gatekeepers to validate what I care about and create. I am my own authority.

My experience in the industry was a catalyst for me. I listen to a lot of Ram Dass, who talks about how challenges are all just grist for the mill and every hardship can be a tool. How hardship can be transformative. My decade of experience as a photo editor is my transformative tool. For years I tried so hard to advocate for artists of color, pitching their work only to be met with denial and indifference. It fueled the fire in me. I knew if decision-makers weren’t listening, I’d have to create opportunities on my own.

Image courtesy of Melissa Alcena

It’s been my anchor. The quote “practice, all is coming” became so true for me. Through all that change—my identity, my job, losing a loved one—the practice gave me the space and discipline to keep showing up for myself. It made me stronger. Ashtanga is a six-day-a-week practice, and I’ve learned so much about adapting and being present. With everything that was happening around me, I had to adapt, and my supportive teacher helped me embrace a restorative practice. But it’s the community, too. We do meditation and pranayama practices each week together. It helped keep me grounded when everything else was falling apart.

If you look at the history of photography, during colonial rule, it was heralded as a way to study different cultures, but in practice, it was used instead to perpetuate bias, racist prejudice, and othering, all of which exemplify the colonial gaze. This kind of imagery affirms racist attitudes and ends up distancing communities rather than bringing them together. It’s voyeuristic.

A good example of White gaze and a colonialist point of view is parachute journalism, which happens a lot in documentary photography. Typically, a White photographer is sent somewhere they have no connection to, like the Bahamas. They don’t know the people, they don’t know the history, but they’re sent somewhere by a brand to capture imagery.

The kind of imagery that they’re going to produce is through an outside understanding and perspective. That could include their own racist attitudes or whatever prejudices they might have—conscious or not. These photographers are on the outside looking in, contextualizing everything they see with a perspective from an entirely different place from the one they are documenting. This results in a very different image from one captured by someone who is rooted in a place, is deeply interested in a place, or has spent time there and can highlight the nuances. When you’re talking about the White gaze, it’s ultimately about representation and power relations. Who is being photographed? What’s the power dynamic going on? To understand, you have to pay attention to who has the power to tell certain stories.

Image courtesy of Alexis Hunley

What it comes down to is the work is just better when you’re asking critical questions, when you’re thinking about the power dynamic, when you’re engaging with the people you’re photographing, because when you don’t do that, the work is tone-deaf and distorted. I can see that right away. I look and think, Oh wow. The person who took that photograph has no connection to what they’ve documented.

Our identities are so nuanced and so complex. And yet the White gaze turns us into object and spectacle, when we are layered human beings with valid and interesting lives. I want LISTO to be an example of how moving photography can be when we empower artists to tell visual stories from within their own communities.

Through LISTO, I try to set an example of the critical approach I want to inspire in other people—regardless of race or ethnicity. For me, there’s a spiritual element, and there’s a practical element, and the spiritual element is about listening and respecting people’s lived experience and having curiosity about it. If I like the work of photographers and artists, I always want to know more. Humanity, connection, and critical inquiry are missing from the White gaze. There’s no stake in other perspectives. There needs to be a space of respect for people’s experience that’s beyond your own race, and that requires being truly interested in another human being and honoring their experience.

On a practical level, it’s about asking questions: If I’m looking at a magazine, I ask: Who is taking this photograph? Why was it commissioned? How was it commissioned? What connection does the writer or the artist have to the space? I think that can be challenging for people. Talking about colonialism can feel daunting, as if there’s no way to escape it, but there is. The way to escape is to be present, to name it, and to be curious.

The artists I speak to are so passionate about where they’re from, and they bring with them such unique experiences, but as they try to forge careers as serious artists, they are treated as names on the list of BIPOC photographers. There’s no conversation about their work or what inspires them, and that leads to a flatness in how we see one another.

Image courtesy of Bethany Mollenkof

I grew up in a world where everything was seen through a White-dominated lens. So when I see work by artists of color documenting their own experiences, to me, that’s directly challenging the White gaze. Another form of visual activism is when any creative, whether you’re a photographer, producer, whatever, seriously considers the ethics of how they’re producing and sharing imagery. This is also visual activism.

My drive is to support and amplify the stories of BIPOC artists, and I personally make it my whole mission, but anyone can be a visual activist. If we are transforming photography from a tool that was historically used to other and exoticize people and we are changing it into one that empowers people, that’s visual activism.

I tell people over and over again: This is not a moment; it’s a movement. And this movement is not just about checking a box and saying, “I hired a Black photographer for this project; the work is done.” No, it’s an ongoing process. When you begin to do this work, it’s important to consider: What is your purpose? What are your values? Check in with these questions at each step along the way.

It’s very similar to having a yoga practice. I’m a total Ashtanga yoga nut now, and I ask meaningful questions in my practice as a way to stay connected and devoted. What is your intention? Are you doing it for ego? Are you doing it as escapism? Or are you doing it with a higher intention? My teacher, Timothy Lynch, talks about the importance of showing up on the mat with all of it: the good, the bad, the fear, the doubt. Embrace it all each day.

Again, it’s all grist for the mill. All the suffering and pain the artists experienced, I feel that, too. For me, it’s a healing exchange of listening, talking with them, getting to know them. I think part of what racism does is that when you’re in a White-dominated space, you feel so isolated. Oftentimes I’m the only person of color in the spaces I navigate in my life. The experiences you have, it all feels so disorienting. You think, Maybe it’s just me; maybe I’m seeing things wrong. When you’re not in the majority, it’s hard to gauge reality. But talking to these artists is an affirmation. It’s saying: Yes, I also experienced this. We hear and we see one another. It’s a restorative experience for me.

Sara Urbaez, a first-generation Dominican photo editor and producer, has spent the last decade building relationships and spearheading movements in the industry to help diversify photography. She is the founder of LISTO, a curatorial platform devoted to BIPOC photographers, and has worked in the photo departments of Wired, Departures, Art + Auction, and W magazine, among others. In her spare time, she volunteers as a full-spectrum doula.