Grieving the Loss of a Life You Wanted

Where there’s a plan for our personal lives, you’ll likely find some kind of backwards math: If I’m going to have this number of kids by this age, I need to be married by this age, which means I need to be dating my partner for however-many years before a however-long engagement, therefore I need to have met my partner…years ago.

Traci Bank Cohen, PsyD, hears a lot of these calculations in her Los Angeles–based psychotherapy practice. She says these kinds of expectations are often not fully met, and that for people who have “done everything right,” feeling like they’re missing something they’d always imagined they would have by now can be destabilizing. It can be a recipe for not just disappointment but something more difficult to cope with: grief.

Most often, Cohen finds that her clients are grieving not having a long-term partner. Other times, it might be children or a career they love. (In this interview, we focus on relationships, but most of the advice is applicable to other situations as well.) What’s difficult about addressing these unfulfilled expectations is that some elements just aren’t within her clients’ control. Cohen can’t promise that the thing they want most will happen for them if they just do x, y, and z. Instead, she works through their pain the same way she would with any loss: teaching self-compassion, acceptance, and openness.

A Q&A with Traci Bank Cohen, PsyD

A big part of what I see, recognize, and validate for my clients is that it can be incredibly painful not to be living the life you had imagined for yourself. While managing uncertainty is part of the human condition—because who knows what will actually happen in the future—it is particularly challenging when you see others in your life who perhaps are fulfilling for themselves the same dreams you have for yourself.

There’s so much effort that goes into figuring out what it would look like to have this life that we’ve imagined. A big part of the work that I do with my clients is helping them to detach from the notion that something must be or look a certain way and helping them ultimately be okay in the not-knowing. In other words, becoming more tolerant of uncertainty. To achieve that, we have to validate what they’re going through and provide them a space to grieve the loss of the life that they had envisioned for themselves.

Because it is grief. We can use the example of relationships: If you’re at an age where you expected yourself to be—or feel that others expect you to be—in a committed relationship, and you’re saying to yourself , “I was okay being single before, and now I’m not, and I want to be in a committed partnership but dating has been a struggle,” that’s a loss, even though it may be invisible to others. You’re not necessarily grieving the loss of a relationship per se (although maybe you are grieving that as well) but grieving the loss of the life that you want and don’t yet have. That can be incredibly painful, and people don’t really acknowledge that.

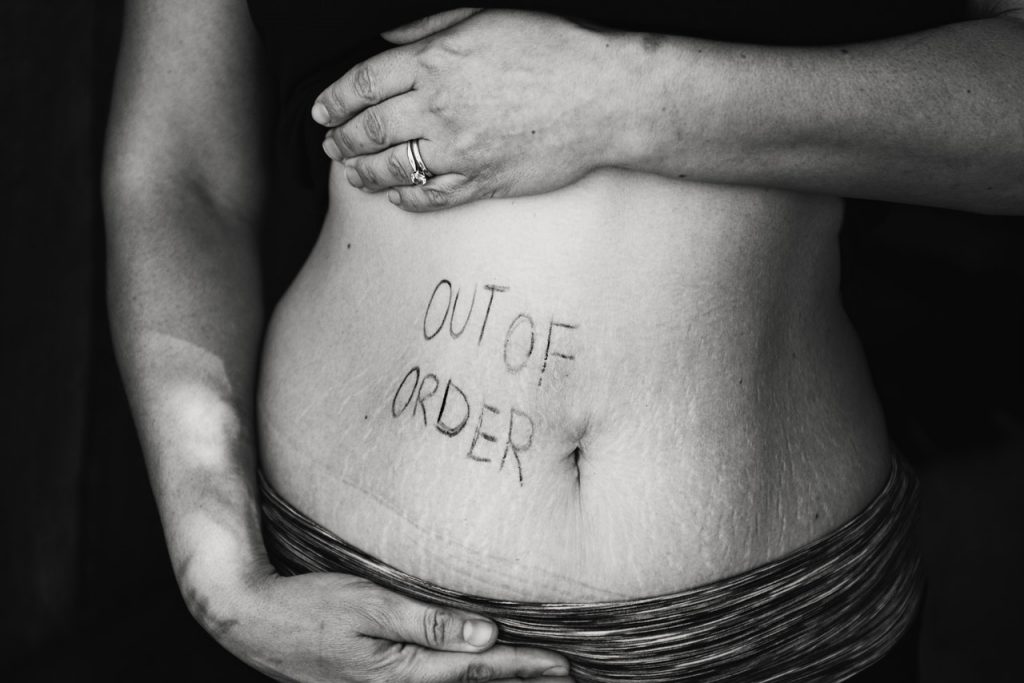

While I’m talking about dating and marriage here, I actually believe this is a feeling that’s applicable to other situations where you’re coping with losing something you didn’t have in the first place: It could be a person who feels totally unfulfilled in the career they’ve spent years building, doesn’t know what they want to do, and is living in that uncertainty. Or it could be a person who wants a biological child and is on a long, seemingly never-ending fertility road. While it’s not the same as having a miscarriage or a stillbirth, which represents the physical presence and then loss of a baby, reproductive challenges can translate to months or years of missed time they would like to have with that child.

It’s important to note that for most clients I see, when this issue comes up, they often don’t seek therapy specifically saying, “I’m not in a relationship and so I’m miserable.” Many come in saying everything’s fine, but they just want to figure out their life. Many of them feel like they need to present themselves in a way that’s really put-together, as if they think they don’t have the right to feel upset about what they’re mourning.

The first piece to this is identifying what someone is feeling and understanding how they relate to that feeling. That may sound basic, but it’s incredibly challenging work, and it can take quite some time just to help someone identify and access their emotions. It’s about practicing authenticity in their experience as it is right now and embracing those feelings: Maybe they say, “I’m just frustrated with the dating scene,” but when you investigate that frustration, you discover together that they’re sad and feeling a loss, or that they’re angry that their friends are in long-term relationships and they’re not, or that there’s an underlying feeling of fear that they’re going to be alone forever. Those are unpleasant things to feel, and so a lot of people avoid feeling them. And I don’t blame them for engaging in that coping strategy. But that’s where we start.

Therapy for this kind of issue is certainly not linear. Instead, we focus on creating a space to process the client’s feelings, do the work around what it means not to have this thing they wanted, and ask: How do we remain authentic in our connection with others and continue to live a fulfilling life even when a part of that life doesn’t feel fulfilled?

I work from an attachment-based orientation. A lot of my job focuses on helping my clients understand their attachment style, and that requires them to look at not only their relationship to their feelings but also their relationship with themselves and what they’ve come to expect from other people. If they’ve had experiences where they can’t rely consistently on others, because of parent-child dynamics or some other reason, processing that is a big part of the work. Sometimes it comes up that they have established dismissive or anxious attachment patterns, and we work to create secure attachment in a way that hasn’t been modeled for them before. Even for people who have more-secure attachment styles, we work on how to build healthy relationships with themselves and with other people.

“So acknowledging that there are elements you can’t control: What are the things that you can control?”

Sometimes, people use their own narrative as a defense mechanism. What I mean by this is that they use past experiences to predict how the rest of their life will unfold and then continue to engage in self-sabotaging behaviors to reinforce this belief. Maybe they’re in a sexual relationship they’re not that into or a romantic relationship they know isn’t going anywhere because the other person isn’t emotionally available. Or they may be highly resistant to online dating or dating in general because they tell themselves it’s not organic enough (I’m not sure what that even means) or that nothing’s ever going to work out.

The individual situations run the gamut of what dating looks like, but it’s all coming from the same place of fear. Because the brain is hardwired to feel threatened by the unknown, people tend to believe the lie that if they tell themselves to expect the worst-case scenario, knowing the outcome—even if it’s not the desired outcome—is better than being caught off-guard and ultimately feeling let down. In reality, expecting the worst may be more of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

I do want to be clear: In no way do I think it’s someone’s fault or that something’s wrong with them, or if they do make these changes that they’ll necessarily meet someone on the timeline they imagine. That’s not how it works. Timing is so important: How a relationship works out is not about the timing of your own life and plan. It’s also about the timing of someone else’s life and your life and whether those two things come together in a way that works.

Whether timing hasn’t worked out or there are more deeply rooted pieces of why someone’s not dating, either way it’s a loss. And either way, it sucks, it hurts, and it’s painful. So acknowledging that there are elements you can’t control: What are the things that you can control?

A big piece is acceptance. It’s a process of grieving whatever loss you’re going through and then moving toward a place of acceptance, of saying: Yes, my life isn’t what I imagined it would be—there’s a piece that feels like it’s missing, and I do feel sad about that—but I am grateful for the things in my life that are working, and it’s okay that I don’t love every part of my life right now.

What makes this so challenging for people is when they resist what’s happening in reality and attach themselves to this plan that isn’t happening. You have to change your relationship to the thing that you want so that your plan is not holding you back from other wonderful things.

It’s also helpful to have someone in your life you can confide in and who genuinely supports you. Just be mindful of whose advice you’re taking. Part of your job being in your experience and in your body is teaching people how you want to be treated. So if you go to a friend to tell them how you’re feeling lonely, and they’re problem-solving for you by telling you—and I hear about this a lot—to try so-and-so dating app, that’s not actually helpful. You have to advocate for yourself. You can say, “I appreciate you giving me these ideas, but what I need is someone to support me and listen to me. I just feel disappointed and sad and frustrated right now.”

“You have to change your relationship to the thing that you want so that your plan is not holding you back from other wonderful things.”

That’s part of why identifying what you’re feeling is so necessary. Because when you show others how you want your needs to be met, you will feel more connected. You will experience some more vulnerability, but you will likely feel more satisfied in your relationships as you get through this period of uncertainty.

I also don’t adhere to the belief of “just love yourself first and then everything falls into place.” Loving yourself is great. I am on board with loving yourself. But telling someone it’s their fault for not loving themselves enough and that when they do, everything will work out is the shittiest advice anyone could give you. It’s just so invalidating.

It is important to distinguish pain from suffering. Pain is inevitable. We all experience pain. (For example: the pain of not getting something you want when you want it.) But suffering is optional. Suffering refers to how we relate to our pain. If we can observe and acknowledge that what we are going through is painful without judging that pain or resisting it, we can move toward acceptance. It becomes less internalized, less shame-based, and more rooted in fact. When we attach a story to the pain or believe that the reason this is happening is because we deserve it or because it’s always been like this and nothing will ever change, that holds you back from so many wonderful offerings your life has in front of you in this moment.

The question then becomes: How do you start to accept that it is this way right now and also acknowledge that that doesn’t mean it’s always going to be this way?

There has to be a little bit of room for hope that you will get the thing you want even if you don’t have it yet. I’ve worked with a handful of women who are in their late twenties or thirties who will bring up the expectations they had that they would be engaged by now and they have never been in a serious relationship. They often ask, “How can I talk about getting married when I haven’t even been on a tenth date with someone?” And what I usually say to that is: “Well, that is actually how life happens, right? We don’t know something is going to happen until it does. You didn’t know that you would get your driver’s license until you passed the driving test. We can only say in hindsight, ‘Oh yeah, of course I knew I was going to get my license.’ But when you were fifteen, you were probably like, Oh my god, what if I don’t pass and I’m the only person in my friend group that doesn’t drive a car?”

But that experience feels so real to us in each moment of our life. We tend to think that we have to have had an experience in order for it to happen, and that’s not how life works. Everything that happens to us must happen for the first time.

Traci Bank Cohen, PsyD, is a licensed clinical psychologist and cofounder of Westside Psych, a group psychology practice in West Los Angeles. Cohen provides individual, couples, and group therapy. She specializes in women’s issues, including eating disorders and disordered eating, maternal mental health, anxiety, depression, and self-esteem. Cohen uses an integrative approach to treatment that combines relational, emotion-focused, and evidence-based practices.